As many of you know, I recently travelled to Canada for a week. It was a work trip to Vancouver, to speak at the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Exploration (SEPI) conference with Dr Jennifer Franklin. A psychologist, Jennifer is part of our professional clinical TMS/PPD list, and we have been involved in several writing projects together, and speak regularly. Even so, I was surprised one day to get a call from her out of the blue. Take a look at the theme of this SEPI conference, she said, I think we would be perfect for this.

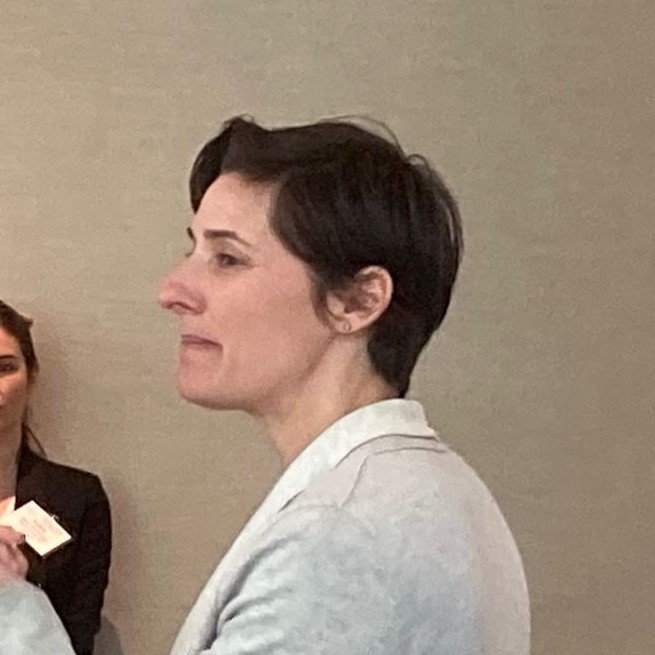

Our skills neatly complement each other, but Jennifer is from Los Angeles, so we had not met in person before. This seemed like a wonderful opportunity to combine making that connection with speaking at the conference. I made the trip over to North America, and Jennifer headed up to Vancouver, ready to speak first thing in the morning on the third day of the conference.

Our workshop was focussed on the importance of feeling safe when working with patients experiencing psychophysiologic disorders. We believe the effective approach is through healing, and to begin the healing process the patient needs to feel safe. It is then possible to address the root causes, rather than be restricted to managing symptoms.

Jennifer began with some thoughtful and thought-provoking exercises about external safety, how to acknowledge the fears we all have when meeting someone new and being in a new environment. I led the section on internal safety, using an experiential approach focusing on four movement and body awareness exercises. We covered posture, ribcage breathing, creating an internal Victorian corset of muscle engagement, and segmental movement of the spine. This linked to another portion about the pedagogy of PPD, focussing on health practitioners working with patients, and the therapeutic relationship between them.

The session was well-attended, and we had some excellent feedback. It seemed people enjoyed being given practical movement exercises they could take with them, as well as some thought-provoking ideas about our approach to teaching how to resolve chronic pain. It was also wonderful to speak to a group of people on the other side of the world who were nevertheless fascinated by the same issues that I speak about regularly with all of you.